Filipino Christmas Cheer as Musical Mourning

Should Christ come back to earth soon, He should consider the Philippines as His place of (re)birth.

Months before the designated date of delivery, His arrival will already be fêted with lots of lanterns and periodic blasting of familiar holiday tunes. This musical atmosphere, stretched for several months, is what gives Christmas in the Philippines its truly distinct temper. But while it is surely festive to almost all, the season can be funereal to some, especially to those in the labour sector. The year-end party is coming close, so prostrate corporate employees stay late in the office just to practise the dance steps to Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You”. Commuters stuck in worsening Yuletide traffic are brimming with rage, Jose Mari Chan repeatedly implores them to fill their hearts with Christmas cheer instead. Tired and exhausted workers toss and turn in the dead of night, unable to sleep, as their neighbour kindly lulls them with a karaoke rendition of Wham’s “Last Christmas”. It’s the season of giving, after all, but little regard is given to consensual reception.

To outsiders, this extended celebration must feel like an aberration. But for those born and living in the country, the normal run of things is to welcome the coming of baby Jesus right at 1 September, which is why it is often dubbed the “Longest Christmas in the World”. Many have tried to decode the underpinnings of this phenomenon, and, of course, those in the academe have thrown many explanations as well. Professor Ed Timbungco of De La Salle-College of St. Benilde says that it is because Filipinos “don’t want happy moments to end.”

Okay, that sounds reasonable enough. But almost all human beings want to indulge in a state of delight, and a great many would, without a doubt, do all that they can to prolong the experience, so it is not at all convincing. But there’s something in what Timbungco says afterwards that is particularly illuminating: “We look forward to family gatherings and reunions so we can make up for lost time.”

This “lost time” is crucial in understanding the motives of Filipinos in celebrating as much and as long as they can. With it comes the problem of “distance”, the brutal barrier that prohibits people from spending their passing hours together. Two (or more) persons yearning for each other’s touch can experience the same sunset at a given hour, but be a thousand kilometres apart. So Filipino Christmas is heavy with the theme of physical reconnection, of filling the void left by spatial and temporal separation. This partly explains why Filipinos already begin Christmas preparations in September: because reconnection implies coming “home”, and that means travelling to and/or in the Philippines, which is expensive for most, and impossible to many. Months of planning and many thousands of pesos are required to see familiar faces again even just for one day.

To help relieve the joint arthritis of absence and longing, Filipinos turn to the soothing sway of music. This is why it is central to the Philippine Christmas experience, because music is the way by which the soul amplifies its silent screams. For underneath this physical need to reconnect is a spiritual impulse, an inner mandate of the individual soul to feel the comfortable familiarity of those who’ve been away. Music is the language by which the soul communicates its anguish and solace: melodies give it grammar, tempo adds cadence, notes form its words, so songs are complete declarations of spiritual intent. “[I]t is the art of the soul,” says the eminent German philosopher GWF Hegel, “and is directly addressed to the soul.”1

While physical vibrations produce sound that collectively form into what we perceive as music, its immaterial qualities penetrate skin and bones to stir the cradle of our souls, which our minds then make sense of to derive emotional and intellectual fulfilment. But this philosophical appraisal did not just arise the very moment humans emerged from the Hominid branch as a new species, but rather, as with all things, it developed through time, that is to say, it has a history. And for Filipinos, especially the Visayans, the deep appreciation for the powers of music goes way back to the time before colonisation.

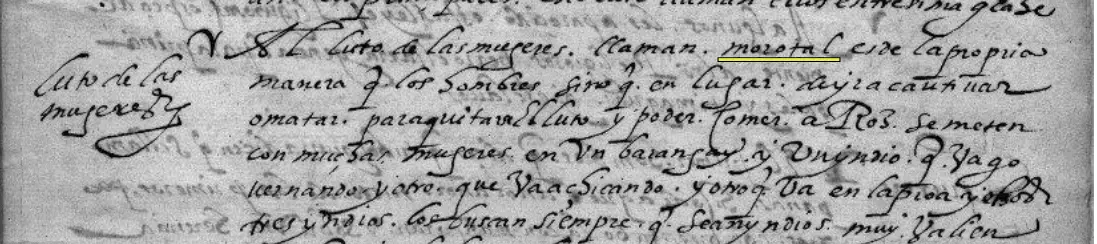

In his 1582 Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas, Miguel de Loarca writes that one of the ways Bisaya women mourn their dead was through a riverine procession called morotal, where a grieving woman gets on a balangay with other women from the village and then have three men row the boat down a river. As they cruise, the men sing lamentations, recalling their exploits and the people they exploited. (Mention of the morotal in Loarca’s text can be seen in the image below.)

It is extremely unfortunate that no such record of ancient Bisaya eulogia exists today. We will never know the words to their songs, making it impossible for us to comprehend how they utilised language as a vessel for their grief. However, the essence of the practice managed to escape total colonial erasure. It has survived and undergone various evolutions across time. Town records from the 1950s report that in the island of Negros, a form of collective singing called “bilasyon” was observed during wake services. This form of recapping the deceased’s time on earth through songs may be likened to today’s trendy Spotify Wrapped, only, with a lot less unwarranted collection of personal data.

Security concerns aside, this propensity to encapsulate memories in and through songs is helpful in fully understanding the musical mourning latent in Filipino Christmas. Past lamentations were almost exclusively sung to remember the people who have died. Nowadays, these sorrowful songs are also dedicated to the people who leave but still live, that is to say, who are still alive but are far away. This novel turn has been strongly engendered not by a cultural shift, but by the need to adapt to the increasingly sombre economics of modernity.

In the ancient past, most bonds were severed by diseases, weaponry, and warfare. Today, the primary cause of social dissolution is often a domestic reflex to the dictates of capital, which forces families and friends to depart and seek fortunes elsewhere, lest they rot in their country which has no intent of helping them survive. In the Philippines, this humid burden was made more suffocating by the senior Ferdinand Marcos, whose sickening rule slumped the economy and made the lives of millions of Filipinos worse. As president, he borrowed money from foreign banks to fund his projects and support his cronies. To pay them back, he had the brilliant idea of borrowing more: getting new loans to pay for old ones.2 This made him, his family, and his friends happy, but this miserable loop eventually crippled the country’s economy. So what did Marcos do as a response to the worsening economic state of the country?

Apply for more loans.

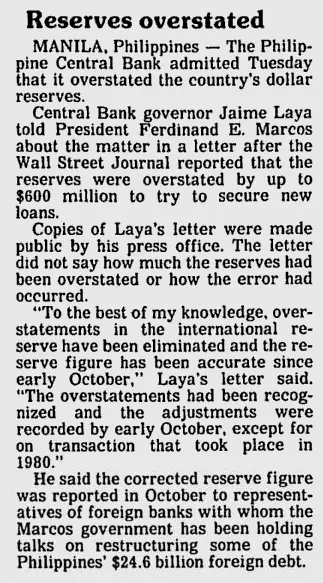

There was a problem, however: confidence on the government’s ability to pay was shrinking, and when the creditworthiness of the Philippines waned to an embarrassing low, something had to be done, regardless of the means. To convince bankers and investors that the country was still more than capable of paying their outstanding balances, the Philippine Central Bank, the personal piggy-bank of the president, issued a report that its dollar reserves amounted to $600 million, a staggering amount for sure, enough to dispel the general skepticism. However, the bank was soon exposed for faking its data, because no such quantity existed.3 What was evident and required no fraud to show, was that the country was already drowning in debt. Who was to pay the totality of these loans including their interests? Not Marcos and his cronies, obviously. So who would shoulder the burden? The ordinary Filipino citizens, of course. When it had become clear that life in the country wasn’t getting any better, many made the difficult decision of going abroad to to be an Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW). “[I]t was when Martial Law was declared in 1972 and the years after when mass migration of Filipinos to different parts of the world took a quantum leap”, says Ted Laguatan in an Inquirer column. Data from the period corroborate this claim.

News clip from The Spokesman-Review, 23 December 1983.

Filipino labour migration to more prosperous countries had long been underway even before Marcos Sr. won the presidency in 1965. But what he did was to utilise this momentum, spurred by the growing inequalities he effected, to maximise whatever economic and political profit he could squeeze out of sending Filipino workers abroad. From 1974-1985, coinciding with the time Laguatan mentions, about 2 million Filipino workers left for either the United States or the Middle East; around 120,000 landed in Western Europe to work mostly as domestic helpers and medical assistants; and about 57,000 Filipino seamen left the country’s shores.4 All in all, a countless number of families losing beloved members not because of death, but because of living in the Philippines.

So while the economic forces that keep families apart remain, expect more and more Filipinos to leave the country for better chances abroad. And as things worsen in a Philippines headed by another Marcos, many OFWs have no other choice but stay in their country of work and postpone their homecoming. It’s the same old tune as before: more Christmas celebrations will be held with a missing family member or two.

In fact, this domestic configuration has been so entrenched in Filipino society that it has modified traditional relations and expectations within families. A 2011 study found “no evidence of poorer psychological well-being among Filipino children in transnational households compared to children in nonmigrant households.” This seeming indifference among children, the researchers surmise, is perhaps due to “the normalization of transnational families, especially in the high out-migration areas from which our sample was drawn”.5 That is to say, households with an adult member working abroad were so common that is has become an ordinary experience for local children. To work in other countries, forced or otherwise, meant being able to send remittances back home to meet the household needs. This financial security, it can be argued, replaced the social importance of physical presence, which can hardly feed hungry mouths in the Philippines.

More than a decade later, the literature seems to show a grim development. A scoping review from 2022 reveals that left behind children of OFWs “often adopted poor health behaviours, such as over-eating, alcohol misuse, smoking, illicit substance use, and experienced untimed pregnancy.” As for their mental well-being, the data shows that parental absence is “most likely to be associated with feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and melancholy among Filipino children.”6 So while it may be nice to receive funds to buy the deluxe edition of Depeche Mode’s Violator, it can be a devastating experience to listen to its hit second single “Enjoy the Silence”, especially when there’s the deafening noise of absence inside the house.

The agony of celebrating Christmas away from loved ones is intense and harsh, which for some OFWs feel “like piercing our hearts until it stops beating.” With the heart hardly able to keep its rhythm, perhaps it is music that helps lonesome Filipinos keep and fill time: time “lost” due to forced economic separation.

Should Christ come back to earth soon, He should choose another country as His place of (re)birth if He wants to grow up with a complete family by His side.

-

Georg Wilhelm Hegel, Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art vol. 2, trans. T.M. Knox (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), 891. ↩︎

-

Robert Dohner & Ponciano Intal, Jr., “Debt Crisis and Adjustments in the Philippines” in Developing Country Debt and the World Economy, ed. Jeffrey Sachs (Michigan: University of Chicago Press, 1989): 174. ↩︎

-

Rene Ofreneo, “The Philippines: Debt Crisis and the Politics of Succession”, Philippine Sociological Review 32, no. 1 (January-December 1984): 8. ↩︎

-

Norris Falguera, “Harsh policies spur Filipino labor migration”, Manila Standard, 4 August 1899. ↩︎

-

Elspeth Graham & Lucy Jordan, “Migrant Parents and the Psychological Well-Being of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia”, Journal of Marriage and Family 73, no. 4 (August 2011): 781. ↩︎

-

Georgia Dominguez & Brian Hall, “The health status and related interventions for children left behind due to parental migration in the Philippines: A scoping review,” The Lancet Regional Health: Pacific 28, (2022): 7. ↩︎