The Divine Supremacy of the Goddess Canlaon

One universal axiom goes: when there’s smoke, there’s fire. Science says not all the time, but it’s a good precaution to keep in mind, lest one gets heavily burned. Filipino cinema has a very graphic but convincing case for the axiom’s truism, and that’s from the 1995 version of the horror classic Patayin sa Sindak si Barbara, where there was indeed no fire, at least at first, but the disregard for the smoke’s warning eventually resulted in an actual hell: a sea of flames. Dagat-dagatang apoy.

Ruth, the film’s vengeful spirit, played by the evergreen Dawn Zulueta, had already committed several frightening feats, enough to cast distress and confusion among the inhabitants of her house (but much deserved approval and cheer from the audience). However, these spooky antics were relatively tame, merely child’s play compared to the series of events that were about to unfold.

Child’s play, indeed, because she began her menacing turn with just that. Using her daughter’s dollhouse, Ruth raised an ominous signal, warning everyone that things were about to go down. Up. Right. Left. Just about everywhere.

Smoke puffed from the chimney of the dollhouse.

On 3 June 2024, the island of Negros saw a similar omen. The island’s beloved volcano, Canlaon, erupted around 7 in the evening of that day.

Smoke rushed out of Canlaon’s lips.

While what was, and is still, seen coming out of Canlaon is “smoke”, it’s actually a mixture of many things such as water vapor, escaping gasses like carbon dioxide, and various solid debris, forming a visage that is simultaneously ominous, spellbinding, picturesque, and hazardous. And, like smoke, it was a sign of things to come.

In politics, a few days later a decision was reached to unite the provinces of Negros Occidental and Negros Oriental into one administrative region. Geologically, it was a prelude to a louder chorus. On 9 December 2024, the island once again shook, but this time, to greater degree, as Canlaon exhaled a more explosive eruption. Historically, this series of events may be considered a divine decree, especially to precolonial Visayans who considered the volcano as the abode of their supreme deity named Canlaon.

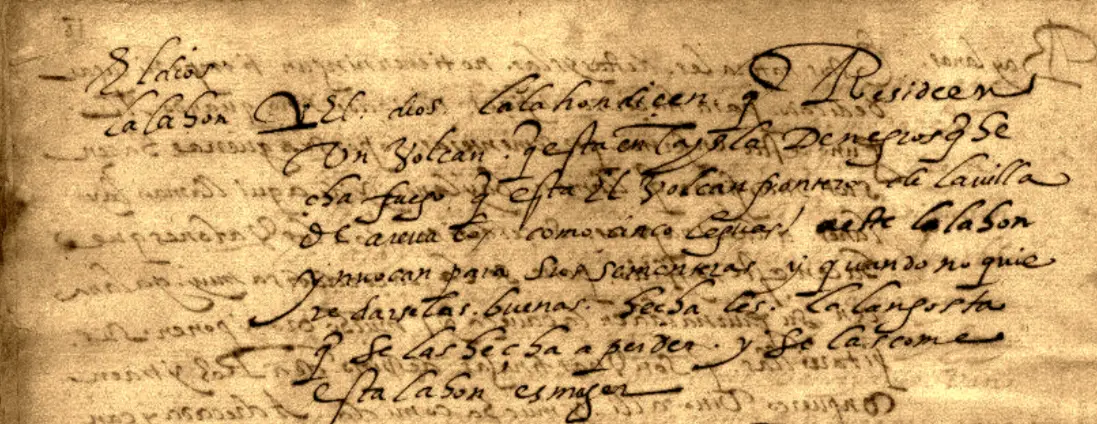

Entry for Canlaon in Miguel de Loarca’s 1582 Relacion de las islas Filipinas. The goddess’ name is spelled as “Lalahon” in this document.

Entry for Canlaon in Miguel de Loarca’s 1582 Relacion de las islas Filipinas. The goddess’ name is spelled as “Lalahon” in this document.

The earliest extant iteration of Canlaon’s name and attributes can be found in the 1582 Relacion de las islas Filipinas by the Spanish soldier Miguel de Loarca. In it, Loarca writes that Canlaon (written as “Lalahon” in the text) lives in the volcano in the island of Negros and has pyrokinetic powers (“que hecha fuego”, makes fire). This capability for combustion is probably an ancient attempt to define a causative agent for volcanic eruptions. An early scientific explanation, so to speak. The document goes on to say that people implore her to save their good crops from locusts (“langosta”). Moreover, and most important, Loarca ends his account of Canlaon with an emphatic statement: Canlaon “es muger”, that is, Canlaon is a woman.1

Canlaon being a woman is an important historical detail that needs to be argued for today, as it gives us an exclusive glimpse into the character of precolonial Visayan worldview. They had no problems assigning a woman with divine status and power. However, in modern iterations of the Canlaon mythos, her stature as a singular goddess is forgotten. Worse, changed. In the collection of local stories titled Mga Sugilanon sang Negros by Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava, the story of Canlaon goes that there was a princess named Kang and a prince named Laon who fell in love with each other and were later buried together. From their graves soon emerged the volcano.

The bifurcation of the name Canlaon into Kang and Laon serves as an effective literary decision, as it easily gives body to discernible yet distinct characteristics. Unfortunately, this leads to two flagrant issues. First, the woman is assigned as “Kang”, which in old Hiligaynon is an article (“can”) for a noun in the oblique case. In this sense, the woman merely functions to give grammatical sense to the name. Second, the name “Laon” is assigned to a man, effectively robbing the historical goddess of the arch eminence assigned to her. This last point is important because her name is quite central to her recognised divinity throughout the Visayan islands.

During his time stationed in the Philippines, the friar Pedro Chirino heard various songs that told tales of the world’s creation, human origins, and other things of interest to precolonial Filipinos. One name stood out in the songs of the Visayans, that of whom they considered as above and superior to all (“principal, i superior de todos”), and that was “Laon”, which meant antiquity (“que denota antiquedad”).2

Chirino doesn’t state whether Laon is a man or a woman. Perhaps he knew, but felt that it wasn’t important to mention. Nonetheless, his description offers a possible explanation as to why unmarried people, especially those in advanced age (“antiquedad”), are called “laon” in various Visayan languages. There’s another way to understand this without demeaning the name into a pejorative. Perhaps they are called “laon” not just because they’re old and alone, but it can also mean that they belong to no one, that they embody the value of independence, which was a hallmark attribute of the goddess herself. This needs further explanation, but a historical example would do. In another authoritative Spanish text, Canlaon’s superlative standing is recognised not just because she’s a woman from an ancient past, but she is also given the role of sole creator.

The Jesuit missionary Fransisco Ignacio Alcina spent three decades of his pastoral work around the Philippines, mostly in the eastern islands of Samar and Leyte. It is there where Alcina heard of Laon’s divinity from the Visayans themselves.

According to Alcina, the Visayans acknowledged “Malaon” as the first cause (“la primera causa”), the one they judged to be the beginning of all things (“al que juzgaban por principio de todo”), in short, the genesis of the universe. This ordinal primacy in-itself is already astounding, but there’s more to Malaon. The deity was also recognised as the greatest and most powerful (“al que reconocían por mayor y de más poder”). Like Chirino, Alcina records that the name is synonymous with antiquity (“El Antiguo”, the ancient). Unlike Chirino, however, Alcina does write that Malaon is a woman, but he has some reservations as to its certainty. This hesitance stems from his frequent communications with the Visayans of Ibabao, who invoked the name of Malaon interchangeably with that of another deity, Macapatag, who was a man, and the selection of which name to use depended on the purpose of invocation. One such example was when they wanted to instil fear (“cuando querian poner miedo”), in which case they used Macapatag.3

Though this might cast wholesale doubt on the enterprise of Canlaon being a woman, there are two things worth considering before reaching a hasty judgement. First, Alcina explicitly states that this is what he had heard from Visayans in Ibabao. Thus, this could have been a regional feature only. Second, by the time Alcina began to compile his three decades worth of notes in 1667, almost all Visayan polities were already under the yoke of Spanish colonial rule, enough to influence local beliefs with that of their own. And, in 17th century Spain, gone were the days when the seat of power was ultimately occupied by a woman, the august Queen Isabel I of Castile. Thus, it is easy to see how the central role of Canlaon in the event of creation is still there, but there is already hesitation to admit that such a cosmic undertaking could have been the responsibility of a woman. This assignment of divine properties with regards to sex may also have set the template for later dilutions of Canlaon’s precolonial prestige. Hence, the unquestioned popularity of the tale of Kang and Laon.

The eventual development of Visayan communities into homogeneous Catholic congregations most certainly helped give currency to gender expectations set by a monotheistic empire.

The outcome—a religious, patriarchal society—had no problems demoting women to lesser roles, while assigning what are considered socially, politically, and culturally significant to men, even in mythologies.

It is perhaps this historical turn and erasure that has led the goddess to give sonic volume to her fury in the form of an eruption.

Ironically, this realisation is even made more poignant by a member of the religious community, the late Bishop Antonio Fortich of Bacolod, who once baptised the island as a “social volcano”.

From the 1800s onwards, the gruesome economic divide between the poor and the rich in Negros, set the tone for the island’s stability.

The wound was first rent then exacerbated by the hacenderos, later to be further aggravated by the Marcos regime.

This festering gash welcomes multiple infections new and old alike, cultivating incredible social tensions among the antagonistic classes of the island.

There’s no telling what will happen to this social volcano once the pressure reaches its ceiling.

Perhaps that’s what Canlaon is trying to tell us with her recent activities. If things don’t change for the better, then she might just erupt in a more violent manner, and most of us will end up awash in lava and/or suffocating in smog. Worse, we all will probably drown in a dagat-dagatang-apoy.

May she be kind to those who have fought and are still fighting to keep her island pristine, but ruthless to those who have destroyed her abode for economic prosperity.

-

Archivo General de Indias, Filipinas, legajo 23, ramo 9, no. 36, “Descurbiementos, poblaciones de españoles.” ↩︎

-

Pedro Chirino, Relacion de las islas Filipinas i de lo que en ellas an trabaiado los padres dae la Compañia de Iesus (Rome: Estevan Paulino, 1604), 52. ↩︎

-

Ignacio Fransisco Alcina, History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands, eds. and trans. Cantius Kobak and Lucio Gutiérrez, vol. 3 (Manila: UST Publishing House, 2002), 218, 220. ↩︎

Did you like what you read? Then consider subscribing to the Bibliotikal newsletter to get immediate alerts on new posts, local history news, and activity announcements.

Share on: