Ang Imo Catupong: Finding Love in Ancient Hiligaynon

A common Filipino way to express approval over a couple’s compatibility is to say that they are “bagay”. It is taken to mean that they are suited for each other. At times, it is even used as a suggestion, that person x is bagay for person y, that they are an ideal pair and thus should be together. For example, one can say that Elon Musk and a trash bin are “bagay”, because they need to be thrown away at some point for the sake of the environment.

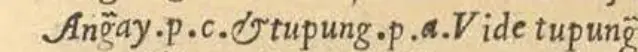

In modern Hiligaynon, instead of “bagay”, the word used is “angay”. So, the Filipino “bagay kayo” becomes “angay camo” in Hiligaynon. But there is a depth to it that hints at a more intimate dynamic, one where compatibility is leveled with being equal. We find traces of this profundity in the 1637 Hiligaynon-Español vocabolario by the friar Alonso de Mentrida. In it, the entry for the word “angay” is as follows:

Mentrida defines “angay” as synonymous with the Hiligaynon word “tupung”, which means of equal measure. Its use varies, frequently associated with physical form. Sports athletes of equal height are said to be “tupong ang cataason”, taas being the Hiligaynon word for height. It can also hold abstract values, like in the ways ability is appraised in Hiligaynon. Someone so talented in a particular field can be described as “wala catupong” (“of no equal”). In its shared consonance with “angay”, perhaps tupong implies that people who are best suited for each other, are those suited to each other: that those who are tupung, equal, to one another, make a better couple.

Although we can’t be entirely sure of a certain equivalence in meaning, we might be allowed a level of inference that hits an agreeable level of accuracy. For that, we need to look to the past where the idea and concept of tupung played a part in forming relationships.

Ancient Visayan courtship rituals and traditions are quite complex and unusual when viewed with today’s biases. Consider, for example, how sexual expectations are set and met in Ancient Visayan relationships. In the Bibliotikal article ‘The Uses of Buyo and Bunga in Ancient Visayas’, Visayan women are shown as having the outright ability to deny or agree to sexual terms with a potential partner. If a man wished to have sexual relations with a woman, he would ask her for a mamá, or betel-nut. When it is offered, it is taken to mean that the woman has given her consent; and when not, it is understood as a clear sign of rejection. But more than just a preamble to the sexual act, women also had the leverage when it came to demanding sexual satisfaction. In ‘Sakit kag Kanamit’, we read reports of Visayan women exclusively having sexual relations with men who had penis piercings, because these genital accessories supposedly heightened their sexual pleasure.

The above examples showcase how tupung might have operated as a subtle Hiligaynon principle in assessing whether couples or potential partners were angayan, well matched. A modern reading of it could be, that Visayan women quite literally asked the men if they could match their freaks. Understood in this frame of thought, tupung becomes less of an equal measure of select criteria, but a concrete setting of terms and expectations. In othe words, tupung suggests that ideal relationships are based on understanding: that the involved parties must first understand what the intentions of each are and what each must give in return to maintain the desired level of reciprocity.

Although faint remnants of such understanding are still present in many relationships today, the premise from which they are observed is different, not anymore informed by considerations of tupung. Instead, they are largely defined at the present by the dominant social relations, which is capitalism embodied by state-nations.

The popular explanation on why most ancient beliefs are gone blames the heavy influence of religions on dominant moral codes, which, in this instance, has supposedly reduced women’s precolonial power to present passivity. But religions can only enact their rules within the confines of their congregations and communities. The broader reach of their beliefs are closely controlled by states which have the monopoly on force. If the state sees that the customs and claims of a particular religion are anathema to its survival, then it is expected that states will look into their arsenal of powers—legal, constitutional, martial—to effectively diminish the influence and numbers of that particular religion. History provides us with ample examples of such measures: after the Reconquista, Muslims and Jews still living in Spain were forced to convert to Catholicism, refusal to do so often meant forcible removal from the kingdom; Hitler and his Nazis exterminated and exiled millions of Jews; and the state of Israel is doing the same to Palestinians in its imperial march to gain greater control of the Levant. But, if the state sees that what a religion asks of their subjects are beneficial to the state, then it sees to it that that religion is protected, or even enshrined as a principal core of the state’s identity. This is the case of the Philippines.

One key feature of the modern bourgeois state is its success in turning all its constituents into mere abstractions, that the population living within its sovereign reach are transformed into equal citizens, and as such, they enjoy the ruthless equality of being equal competitors within the market economy. So, despite the obvious disparity in life expectancies between a rich landlord and a malnourished child of a farm labourer, to the state they are both citizens, equally, and must therefore compete against each other to fulfill their duties as citizens. This creates obvious problems, as not all citizens have access to the levels of wealth enjoyed by richer citizens, but that is not the concern of the state. If the state benefits from having the rich continue being rich, then there is no need for the state to vastly reconfigure its social composition just to accommodate its poorer constituents. In all of history, states have never went so far as to completely disconvenience its ruling class just to soothe the pains of its poor.

But a state that fully abandons its constituents run the risk of losing its most important sector, the force that actually creates its wealth, the workers. Special attention is devoted to the basic need of having workers barely survive the harsh conditions they are exposed to on a regular basis. It is not optimal and excellent care that is given, but only what is necessary to keep them alive. “What could possibly show better the character of the capitalist mode of production, than the necessity that exists for forcing upon it, by Acts of Parliament, the simplest appliances for maintaining cleanliness and health?” asks Karl Marx in Capital.1

It then becomes clear why procreation is a standard demand for couples in many countries, especially where labour is cheap, like the Philippines. For wealth to be created, there needs to be a ready army of workers to be deployed, workers willing to sell their labour-power in a competitive labour market. Among sexually active working couples, intercourse assumes a fundamentally natural function impinged by capitalist pressures, that it is first and foremost a means to increase the economy’s supply of labour-power, and less as a sexually and emotionally fulfilling activity. There is little room to demand for sexual satisfaction when physical bodies are exploied to their limits by labour. This, in the ultimate run, ensures the optimal conditions for capitalism to thrive and survive.

Old values have been violently uprooted to give way for the seeds of capital to grow. If the spirit of tupung is upheld against today’s social demands, then conflicts are sure to arise. The passivity of women (ideally, including men) are helpful to the state as it reduces the threats to its survival. Because if women have the ability to demand tupung, fully able set their standards and demands, that ultimately spells a challenge to the rule of the state; most especially if this remonstrance comes from women within the most powerful and revolutionary sector of the state, that of its workers. It is therefore outside of the Philippine state’s interest that Hiligaynon wage-earning women affirm once again the principle of tupung in setting what they want in relationships and in life.

May we all end up with our catupong, and may all nation-states finally end when they meet their match, their own catupongs, their revolutionary class of workers.

-

Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1890), 452. ↩︎

Did you like what you read? Then consider subscribing to the Bibliotikal newsletter to get immediate alerts on new posts, local history news, and activity announcements.

Share on: